In Ayetoro, faith was not only spoken in prayers or sung in hymns — it was also expressed through the sacred objects that adorned the Holy Apostles’ Church and guided its rituals. These artefacts, simple in form yet profound in meaning, stood as physical reminders of the covenant the community made with God. To worshippers in the 1950s, they were not merely items of wood, cloth, or metal; they were vessels of spiritual presence and symbols of unity in the Happy City.

Among the most revered objects was the staff of authority, often carried by the Ogeloyinbo or senior Apostles during ceremonial gatherings. Made of polished wood, it represented divine guidance and righteous leadership. When raised high, it signalled not only the beginning of worship but also the reminder that decisions and actions were to be taken in humility before God. Elders recall how children watched in silence as the staff was lifted, its meaning instilled in them long before they understood its full significance.

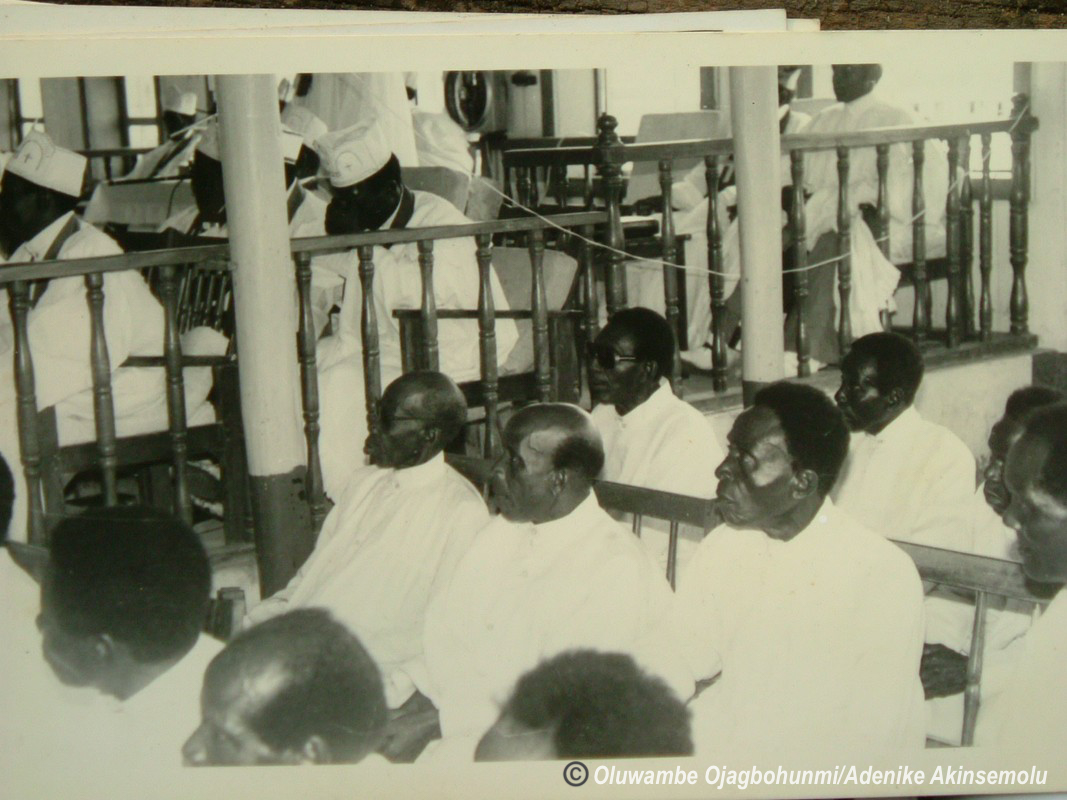

Another central artefact was the altar table, draped in plain white cloth to match the garments of the congregation. On it rested the Holy Bible, opened during readings, and sometimes simple vessels used for blessings. The whiteness of the cloth echoed the community’s commitment to purity and equality, while the table itself stood as the heart of the church space — a place where heaven and earth met in prayer.

Archival photographs and oral testimonies also describe the use of lanterns and candles, which lit the hall during night vigils. Their glow was more than a source of light; it was symbolic of the divine presence guiding the Apostles. To many, the flickering flame against the white garments of worshippers created an atmosphere that felt almost otherworldly. As one elder later recalled: “When the lanterns were lit, the church was no longer just wood and nails. It became a place where God walked among us.”

The hymn books, carefully preserved and shared among worshippers, were another treasured artefact. Their worn pages carried not only songs of praise but also the memory of countless voices lifted in unison. For the Apostles, music was prayer, and the hymn book was its sacred script. Alongside these, drums and other instruments used in services were considered holy tools, consecrated not for entertainment but for worship, carrying rhythm as an offering to God.

To outsiders, these artefacts might have seemed modest, even ordinary. But within the context of Ayetoro, they held extraordinary meaning. They embodied the philosophy that faith needed no extravagance — only sincerity, humility, and devotion. Each item, from the staff to the lantern, was created or chosen by the community, reflecting their self-reliance and deep spirituality.

Today, as the tides have erased much of Aiyetoro’s physical landscape, memories of these artefacts endure in oral histories and photographs. They remind us that the Holy Apostles’ Church was never just about rituals, but about a community that found holiness in simplicity. To remember these objects is to recall the spirit of Ayetoro: a people who built their lives around symbols of light, purity, and faith.