Before the first light touched the horizon and long before the town stirred to life, Ayetoro’s fishermen were already awake. In the quiet hours before dawn, the shoreline came alive with the soft shuffle of feet, the whisper of the tide, and the low murmur of men preparing their nets. To an outsider, it might have looked like simple labour, but to the people of Ayetoro in the 1950s, this daily ritual was the heartbeat of survival and community.

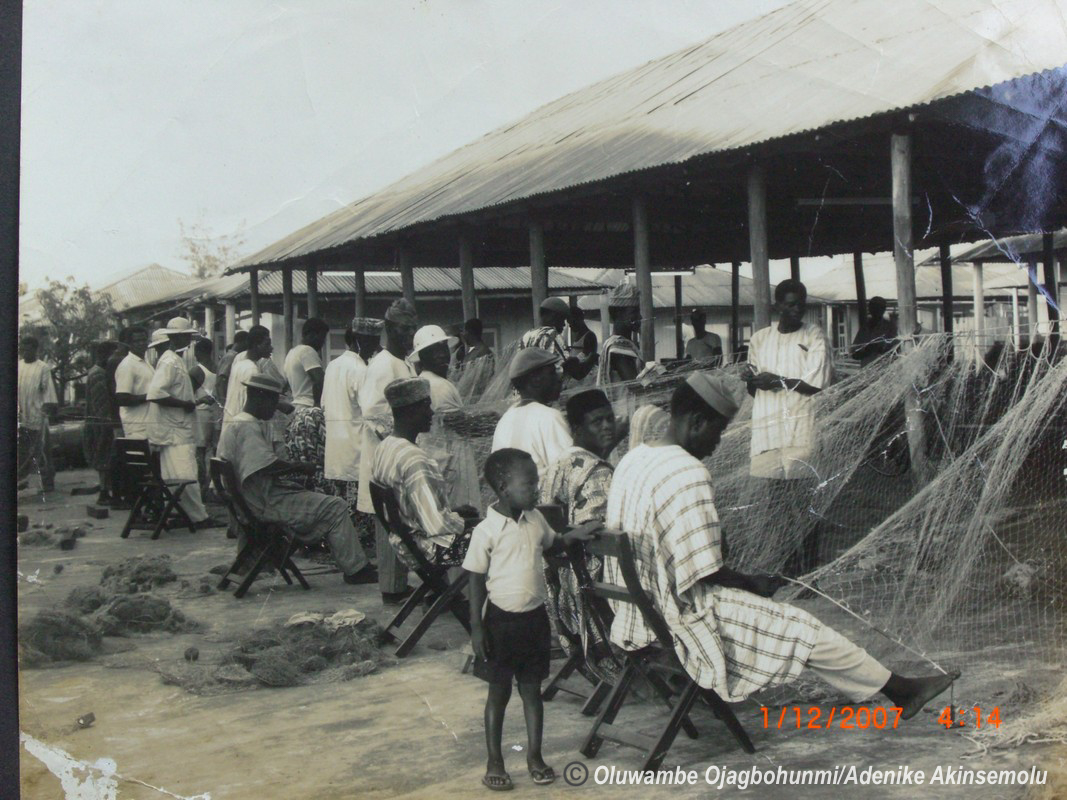

Fishing was more than an occupation; it was the lifeblood of the Happy City. Families depended on the catch not only for food but also for trade and collective contribution to the town’s welfare. Each dawn was a moment of hope — the promise that the sea would once again provide. Archival photographs capture fishermen bent over wide nets, their hands moving with practiced precision, repairing tears, tying knots, and smoothing ropes before heading into the open waters. The air was cool, the sky dark, yet their work carried a rhythm both patient and determined.

Oral testimonies recall that these mornings were filled with quiet camaraderie. Men gathered in small groups, crouching beside their nets laid out on the sand. Conversations drifted between prayer and humour — a whispered hymn, a shared memory, or a joke that sparked muffled laughter. Younger boys, eager to learn the craft, watched intently as fathers and uncles demonstrated techniques passed down through generations. In those hours, knowledge was not taught in classrooms but handed over from hand to hand, knot by knot.

The preparation was as important as the fishing itself. Nets had to be strong enough to withstand the currents yet light enough to be cast swiftly. Floats were checked, weights adjusted, and every thread inspected. A torn net meant a lost catch, and a lost catch meant hungry mouths. The work demanded patience and care, but the men embraced it with devotion, knowing that their labour fed the town and upheld the communal covenant.

As the first faint glow of dawn stretched across the horizon, the fishermen rose with their tools ready. Canoes carved from sturdy wood bobbed at the water’s edge, waiting to be pushed into the tide. Families sometimes gathered to watch their fathers, brothers, and sons depart, waving quietly as the boats slipped into the grey-blue sea. For many children, these departures were moments of pride and awe — the sight of their kin disappearing into the vastness with nothing but faith in the sea and skill in their hands.

Visitors who came to Ayetoro often remarked on the dignity of these fishermen. They saw men who worked without machines or modern technology yet carried themselves with confidence born of centuries of tradition. In their nets lay not only fish but also the continuity of culture, resilience, and the strength of community.

Though the years have brought change, the memory of fishermen preparing nets before dawn lingers in stories and photographs. It reminds us of a time when each day began with labour, prayer, and hope — when the sea and the people of Ayetoro moved in harmony, joined by the humble strength of nets ready to embrace the morning tide.